During the 1930s, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and his Fascist party tried to steer the country away from its dependence on pasta, first by persuasion and then by outright attempts to legally ban it. The move, he explained at conferences, was to protect the wellbeing of Italian citizens – moving away from carbohydrates and focusing on protein was healthier, according to Big Think, a multimedia web portal.

In actuality, the controversial decision was undertaken for economic factors. By the 1930s, Italy, steered by Mussolini’s Fascist party since 1922 and a single party state since 1926, was inflaming international relations. Its botched 1935 invasion of Abyssinia, today known as Ethiopia, and subsequent alignment with German Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler in 1937 and Spanish dictator Francisco Franco in 1939, were incurring financial instability and foreign sanctions.

The mounting cost of flour for pasta, mainly imported from Turkey, prompted Il Duce to seek self-sufficiency in the agriculture and food sectors. Rice, growing in abundance in the northern regions of Lombardy, Piedmont, and Veneto, was to be Italy’s new carbohydrate, according to Big Think. This was the case for other domestically grown products such as tomatoes, olive oil, and wine. Consuming pasta, therefore, was marked as an affront to Italian nationalism. For the anti-fascist partisan movement, the carbohydrate became a symbol of resistance.

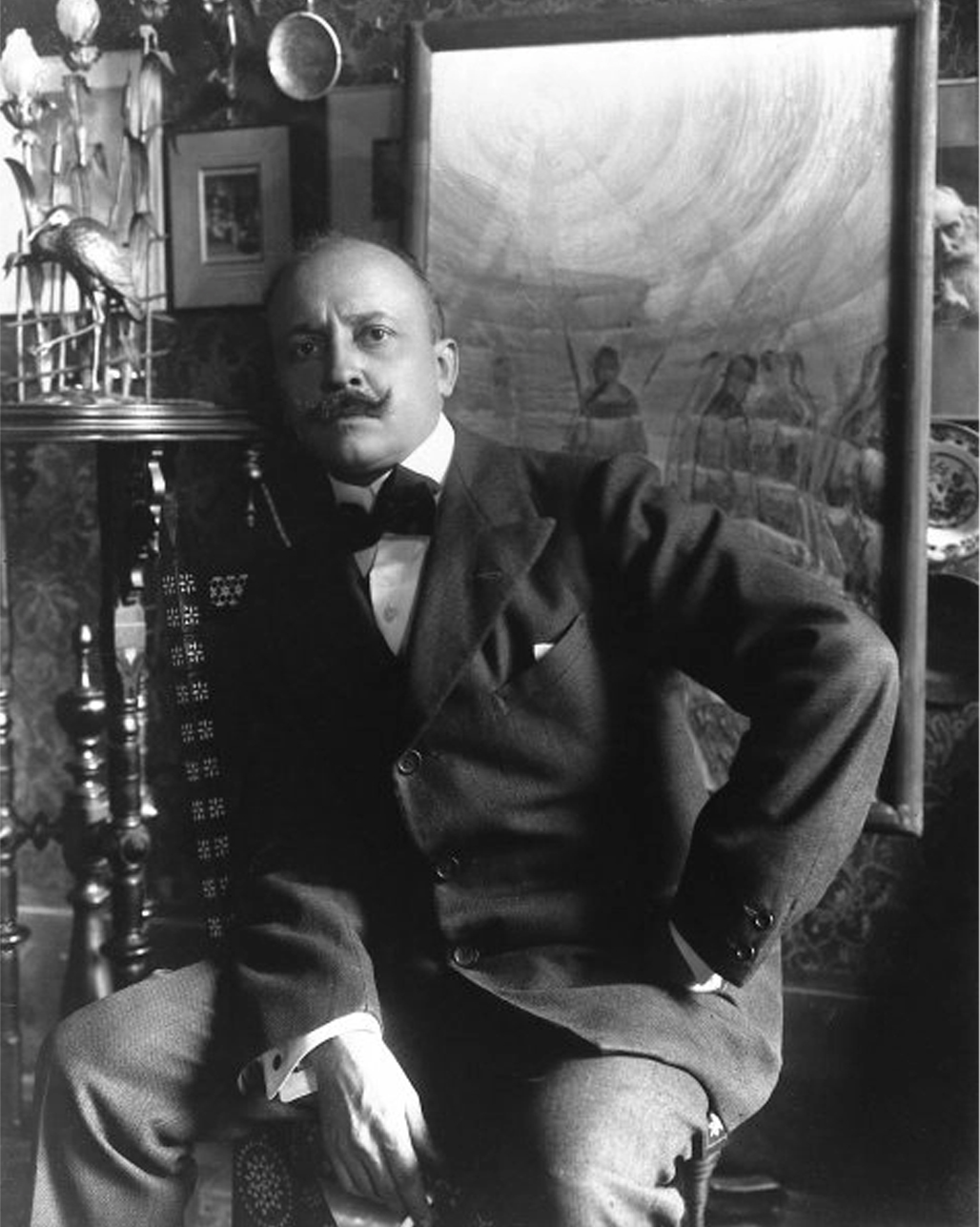

The decision to ban pasta and focus on the perceived supremacy of domestic Italian products was widely supported by the Futurists. Futurism was an early 20th-century social and artistic movement that originated in Italy, according to Britannica. It centered around speed, change, and dynamism while emphasizing violence and conflict. The movement’s founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, advocated for an overturn of traditional values and the destruction of cultural institutions such as museums and libraries, according to Britannica.

While the Futurist movement was founded prior to Mussolin’s ascent to power, it can be considered a precursor to and exponent of Fascism. Historians have generally divided the Futurist movement into two phases: the first, with emphasis on violence and dynamism, began around 1909 and lasted until the end of the First World War in 1918; the second started shortly after during the interwar period and lasted until Marinetti’s death in 1944, according to artmejo, an online arts and culture platform.

The movement and Mussolini, a supporter of the Futurists, were closely intertwined during his ascent to dictatorship, finding common ground in the two major tenets that would become central to Fascist dogma: aggressive expansionism in attempts of becoming a global colonial power, hence the invasion of Abyssinia, and the promotion and preservation of what was believed to be Italian cultural supremacy.

In 1930, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the co-author of the 1919 “Fascist Manifesto,” spoke against the country’s dependence on pasta and outlined the Futurist Movement, and by default the Fascist Party’s, new outlook on cooking.

“I hereby announce the imminent launch of Futurist Cooking to totally renew the Italian way of eating and fit it as quickly as possible to produce the new heroic and dynamic strengths required of the rice,” he said at a Futurist banquet in Milan. Marinetti published an influential cookbook titled “The Futurist Cookbook '' in 1932, advocating for a dependence on Italian-grown rice. “Futurist cooking will be free of the old obsession with volume and weight and will have as one of its principals the abolition of pastaciutta.”

He continued: “Pastaciutta, however agreeable to the palate, is a passeist food because it makes people heavy, brutish, deludes them into thinking it is nutritious, makes them skeptical, slow, pessimistic. Besides which, patriotically, it is preferable to substitute rice.”

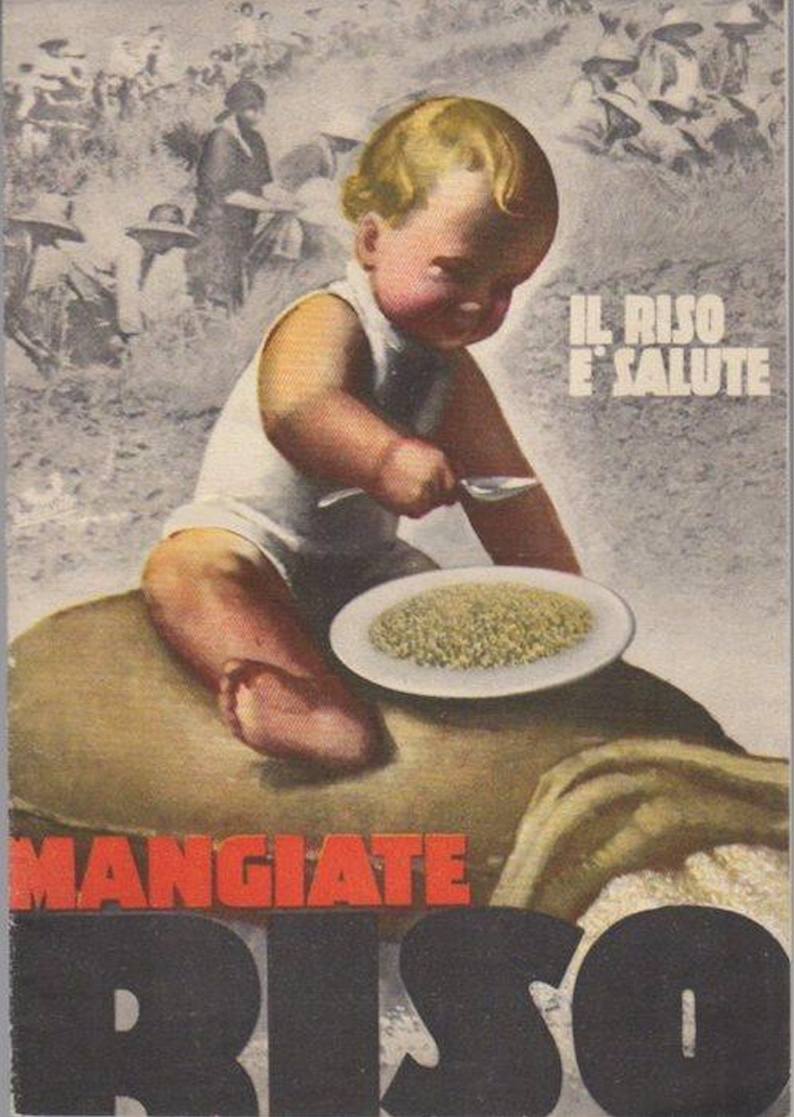

Pasta was deemed unhealthy, while rice was proclaimed its shining antithesis. Consuming domestically-sourced rice made for healthy soldiers and strong mothers, who could give birth to strong babies who would become the country’s next generation of soldiers and mothers.

Not only advocated for in cookbooks and manifestos, at banquets and at conferences, the message was also promoted in ads and posters, which at the time were considered to be efficient means of propaganda. An ad from 1933, for example, depicts a plump, blonde baby seated atop a sack overflowing with rice, eating a bowl of the carbohydrate. The poster prominently features the words “mangiate riso” and “il riso è salute,” meaning “eat rice,” and “rice is health.”

Unsurprisingly, Il Duce’s war on pasta caused a series of labor strikes across the country. According to Big Think, it is plausible that these widespread agitations forced Mussolini’s hand in allowing the country to manufacture pasta. However, the Fascist Party’s inability to replace imported flour with homegrown rice resulted in food shortages leading up to World War II, which had disastrous effects during the war.

Today, as was the case for the brave Italians who defied Mussolini during his 25-year reign, pasta is a culinary heritage and a symbol of pride for the country. Its legacy is so enduring that not even Fascism, food shortages, or a world war could diminish its importance for Italians.

Asia London Palomba

Asia London Palomba is a trilingual freelance journalist from Rome, Italy. In the past, her work on culture, travel, and history has been published in The Boston Globe, Atlas Obscura, The Christian Science Monitor, and Grub Street, New York Magazine's food section. In her free time, Asia enjoys traveling home to Italy to spend time with family and friends, drinking Hugo Spritzes, and making her nonna's homemade cavatelli.