It's only Parmigiano-Reggiano if it's from Parma and Reggio Emilia, otherwise, it's just hard, crumbly cheese. Like champagne in France, Parmigiano-Reggiano is a government-backed, protected term in Italy, and the famous cheese today can only be produced in specified areas. These regions track where it was traditionally produced and dairies follow strict protocols. Outside of Italy, the term has trademark protections.

The king of cheeses has been produced for nearly a millennia, although the stringent rules on what can be called Parmigiano-Reggiano only evolved in the 20th Century. For much of history, the word Parmesan was used interchangeably in English.

Parmesan, whether produced in Italy or elsewhere, is a hard, low-moisture, aged cheese. The cheese wheels are made from small, rice-sized curds and these result in a crystalline, granular structure in the cheese. The Italian word grana, meaning grain, is used to describe this style of cheese. For many centuries, Formaggio Grana Parma or Formaggio Grana Reggio were cheeses made in those towns with a granular structure, not unlike Grana Padano.

Grana Padano is a similar cheese to Parmigiano-Reggiano. Some Italians, especially from Padano, might suggest it’s an even better cheese than Parmesan. Like Parmigiano-Reggiano, Grana Padano is a protected term and must be produced in specific regions. The main difference between the two cheeses, other than the specific land the cows can be raised on, has to do with what the animals eat. Parmigiano-Reggiano cows must eat cereals and grass, while Grana Padano includes silage, a preserved grass feed.

Today, there are about 350 or so dairies producing legal Parmigiano-Reggiano in five regions making up the historic zone. The minimum age for a wheel of Parmigiano-Reggiano is 12 months.

Ancient History

Cheese resembling modern parmesan first appeared in Italy in the Middle Ages, around the 12th century. Monks at the Benedictine monastery of Corniano are thought to have created the recipe, and the first use of the term Parmigiano-Reggiano came a century later. The cheese was often still referred to as Grana Parma interchangeably.

By the Renaissance period, agriculture on the Italian peninsula was expanding once again. The centuries between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance had been marked by instability, and agriculture suffered as a result, but by the 1500s, swamps were being drained to expand fields and pastures.

Parmesan cheese expanded into a regional export commodity. By the 18th century, Parmesan was sold in London and colonial America. The term Parmigiano-Reggiano was not in common use, with the word parmesan referring to hard Italian cheese. Variations of Grana Parmigiano and Reggiano Grana were used in retail and advertising.

The Process

Producing legal Parmigiano-Reggiano requires following strict procedures and the process is slow. The milk is coagulated with rennet, and these curds are sliced into rice-size pieces.

The small curds produce the granular structure, and it’s that crystalline structure behind the grana term. The liquid is then heated in copper cauldrons to activate bacteria that will make the cheese, and the chunks sink to the bottom. According to the Washington Post, the copper must reoxidize for more than half a day before the kettles can be used to make the next batch of cheese, slowing production.

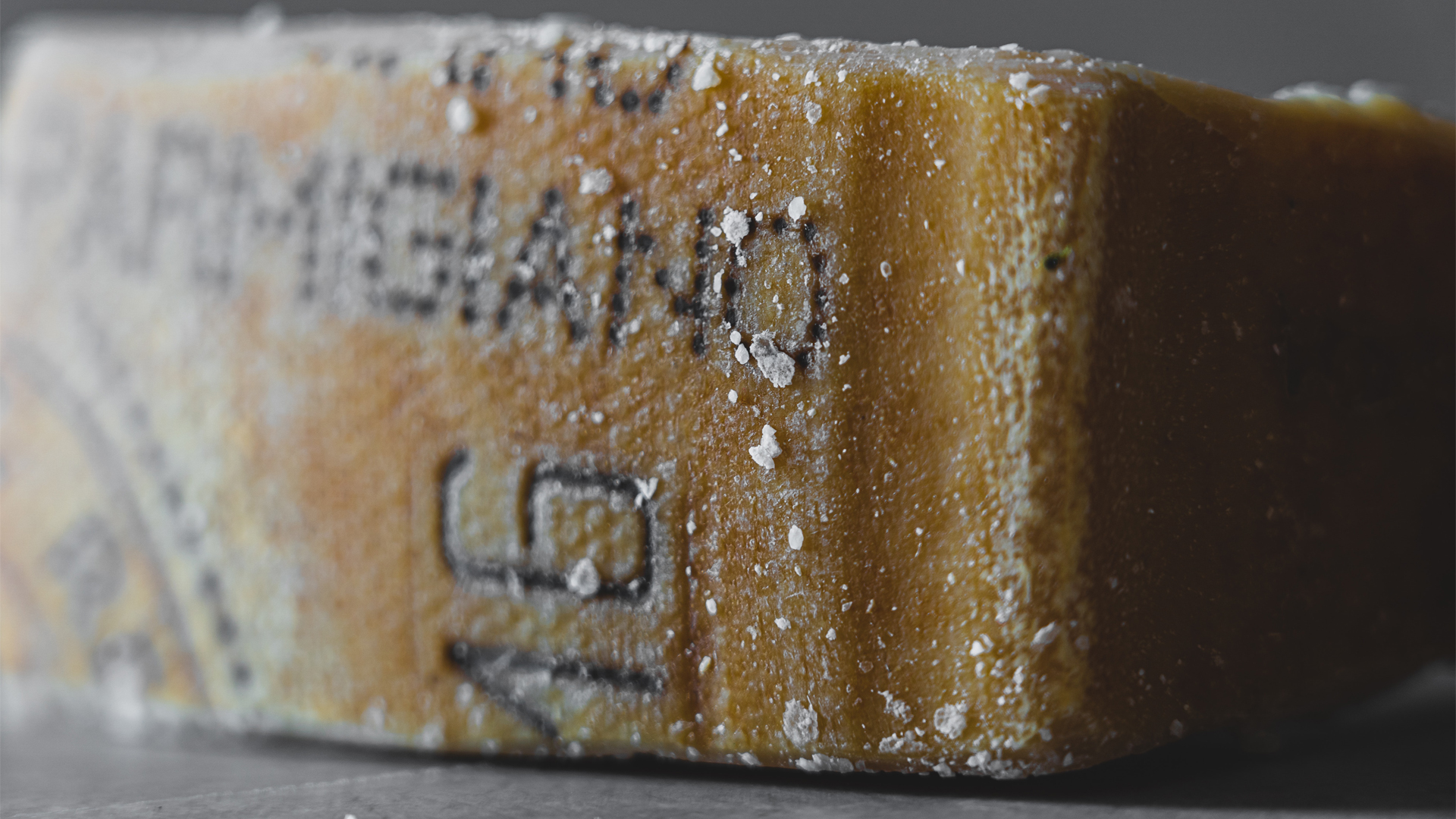

The curds that collect at the bottom of the kettles form a mass that will eventually become a Parmigiano-Reggiano wheel. The curds are pressed into molds to form the shape and receive the maker's imprints along the rind. After a day or two in the molds, the cheese is hard enough to keep its shape and then heads to a salty brine bath where they rest for about a month.

The brined cheese then heads to the aging rooms. The cheese is stacked in tall shelves and must age at least 12 months. The process causes proteins in the cheese to form long chains giving the cheese a rich nutty flavor and a crystal, flaky structure. Many wheels in Italy are aged for two or three years, and very expensive cheese might age for four to eight years. Throughout the process, the cheese is inspected to make sure it is up to standards.

Parmigiano Becomes a Legal Term

Hard cheese like Parmesan traveled well and at least by the 18th century was available in London, and it even arrived in New York a century before Italian immigration. It was still then largely known as Parmesan, even when Italian immigrants began settling in the United States.

Italian American newspapers serving the immigrant communities were the first to mention Parmigiano and Reggiano cheese in 1900, two decades after mass immigration began. The term wasn't an official phrase yet, and modern production regions hadn't been established. More frequently, these cheeses were still known as grana Parmigiano or Reggiano grana.

Since Parmesan had grown into a commodity cheese, Italian producers began looking for ways to differentiate their products. In 1901, the Chamber of Commerce of Reggio Emilia proposed a trade union to protect the interests of producers. Various proposals were drawn up over the next decades, and in 1934, dairies from Parma, Reggio, Modena, and Mantua agreed on the term C.G.T. Parmigiano Reggiano.

By the 1930s and early 1940s, Italian immigrants were beginning to set up dairies in places like Wisconsin to explicitly produce Italian-style cheeses. They set up dairies like Sartori in 1939, Eau Galle in 1945, and Saputo in 1954 in Montreal. BelGioso came later in 1979.

Italian immigrants in Argentina were starting to compete with cheese from Emilia-Romagna in the early 20th century too. Reggianito, a grana-style cheese produced there, is named for Parmigiano-Reggiano but is made with smaller wheels. It has similar qualities in flavor and consistency. By the end of World War I, Reggianito was also posing a threat to Italian cheesemakers.

In post-war Europe as the continent moved closer together, the production of locales was seen as under threat. For the same reasons, Italy set up protective production zones for wine like Chianti's DOC, and the Parmigiano-Reggiano consortium was doing the same for the cheese. By 1964, the remaining dairies signed on.

The Wisconsin Controversy

Earlier this year, Italian academic Alberto Grandi told the Financial Times that he believed traditional Parmigiano-Reggiano more likely resembled cheese produced in Wisconsin. Unsurprisingly, this statement led to some angry Italians.

Modern American cheese production is highly industrialized. It’s unlikely those methods resemble Parmigiano production dating back a century, and the protected system of Parmigiano-Reggiano maintains many of the historic techniques.

Ian MacAllen

Ian MacAllen is America Domani's Senior Correspondent and the author of Red Sauce: How Italian Food Became American. He is a writer, editor, and graphic designer living in Brooklyn. Connect with him at IanMacAllen.com or on Twitter @IanMacAllen.